Collingwood Cult Figures: Phil Carman

Phil Carman: The man Lou Richards branded “the most exciting footballer ever to play with Collingwood ... and possibly the best."

By: Michael Roberts, Collingwood Historian.

When Phil Carman arrived at Collingwood in 1975, many were quick to brand him the most exciting and talented footballer to wear the Black and White jumper in 20 years. But he also proved to be every bit as exasperating as he was brilliant. And that combination has ensured, to this day, his standing as a fan favourite – but a favourite who could, and should, have achieved so much more.

Carman first came to the attention of Collingwood talent scouts in 1965, when the Magpies played a practice match in his home town of Edenhope against a combined League representative side. Carman was only 15 at the time, and was in just his first season of senior football with Edenhope. His performance against Collingwood that day was good enough to earn him an invitation to train with the club for a week during his school holidays.

But Norwood, in South Australia, offered to put him through college to gain his leaving and matriculation, and Carman jumped at the chance. Collingwood refused to clear him (Edenhope was in their zone), but his family moved to Adelaide and the Australian National Football Council issued him with a permit anyway. After half a season the permit was revoked and Carman had to stand out of serious football for the next two-and-a-half years.

As the ban dragged on, Norwood became increasingly angry at Collingwood’s obstinacy, and the Pies eventually granted a clearance on the condition that if Carman ever played VFL football it was to be with Collingwood.

Over the next five years Carman’s name lingered tantalisingly in the background at Victoria Park. He was always going to be coming “next season”, but he never did. Any time Collingwood made an offer Norwood matched it, so Phil stayed in South Australia. By the time he felt he had outgrown South Australian football and was looking for new challenges he was 24 years old.

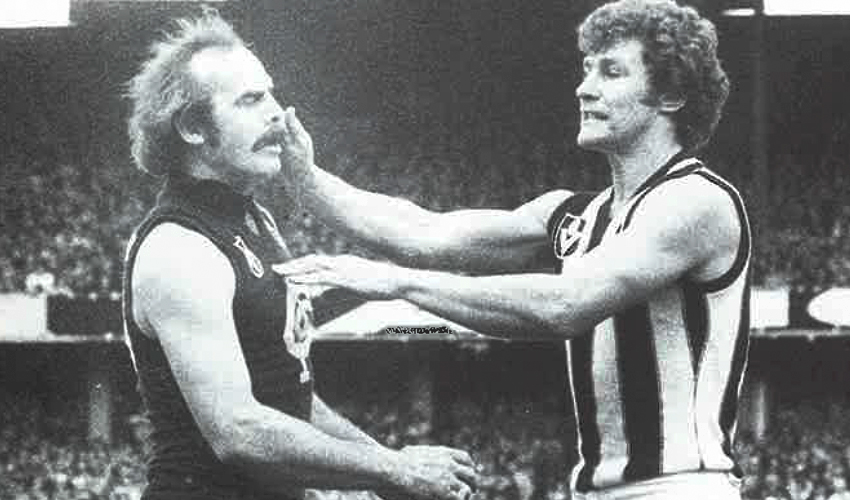

Scrapping with Carlton great Alex Jesaulenko.

After all the years of waiting, Collingwood was abuzz with expectation. Could he possibly live up to the hype? You bet. Despite the burden imposed by such expectations — and a substantial price tag — Carman took the VFL by storm. His performances in that first season exceeded the expectations of even the most optimistic Collingwood supporters, and immediately stamped him as one of the League’s true superstars. He played just 15 games but still won the Copeland Trophy and would almost certainly have won the Brownlow Medal too but for the games he missed (he eventually finished only three votes behind Footscray’s Gary Dempsey).

Carman was a football freak; at his best there was nothing he could not do. At 188cm (6ft 2in) he was tall enough to hold down key positions like centre half-forward and full-forward, yet he was agile and quick enough to play his best football in the centre. He had a huge leap, sure hands, was superbly skilled on both sides of his body, superfit and had a penchant for the spectacular. He was also flamboyant, loved getting in opposition faces, and was responsible for the emergence of white boots.

Collingwood went “Fabulous Phil”-crazy in 1975. He instantly became the biggest and most popular Magpie, and one of the biggest stars in the game. After just 10 games he was chosen to play for Victoria, but broke his foot during the game. Collingwood’s fortunes plummeted without him, but his return to the field late in the season was something extraordinary, even by his standards.

In his first game back he donned the famous white boots for the first time and kicked 6.8 against Essendon in a superb performance. The next week at Moorabbin he simply tore St Kilda apart. In a one-man rampage that will never be forgotten by anyone who saw it, he bagged 11 goals. In its aftermath Lou Richards branded Carman “the most exciting footballer ever to play with Collingwood … and possibly the best”.

At the end of 1975 it seemed that only injury could stop Philip John Carman from dominating the VFL for the rest of the decade. He was in the prime of his football life and was already regarded as the most exciting footballer in the League, and had a talent that would not be matched again until Gary Ablett Snr hit his straps in the 1980s.

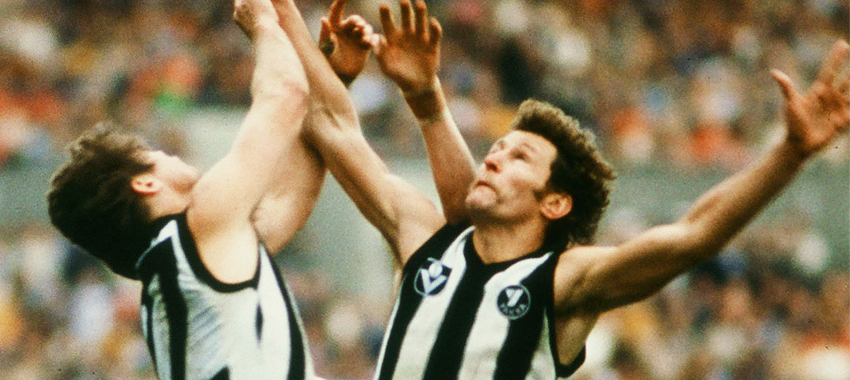

On the fly during his brief but brilliant 66-game career.

But the “Phil fever” that had hit the competition in 1975 had disguised a few weaknesses. He was undisciplined, had a poor attitude to training and little regard for team disciplines. He suffered more than most from the infighting that plagued the club in 1976, and later admitted that he “couldn’t be bothered” with it all that year. He was something of a loner who ran his own race, and would sometimes leave training early when he felt he’d done enough (he was a fitness fanatic who was almost always first on the track). Internally, resentment towards him grew.

“I was irresponsible and undisciplined,” he said in 1991. “I just lost interest — I’d train to maintain my fitness and do what I thought was enough and then I’d sort of wander off. I hated the team meetings and that sort of stuff because they became so repetitive.”

Carman admits his problems were largely of his own making, but he also believes that other players were reluctant to accept him from the start, possibly because of the publicity surrounding his arrival.

Carman found it hard to shake himself out of the bad habits he’d got himself into in 1977, even with new coach Tom Hafey at the helm. But he still became a key to the team’s success that year. He played good football, became a far better team player and remained one of the few Magpies capable of single-handedly destroying an opposition side. But he whacked Michael Tuck in the Second Semi-Final against Hawthorn and was rubbed out for two games – missing both the Grand Final and the subsequent replay. Many Collingwood people, including Hafey, believe his absence made the difference in those epic contests against North Melbourne.

Those same people found it hard to forgive him for that indiscretion, and he was traded to Melbourne after a disappointing end to the 1978 campaign. After that he went to Essendon and North, but he never again exhibited his 1975 form. In fact his most noteworthy post-Collingwood performance was when he headbutted boundary umpire Graham Carbery in 1980 while at Essendon (for which he copped a 16-week suspension).

After he left the VFL, Carman headed bush — but he could not escape controversy. Every so often reports would drift back about another tribunal appearance, going AWOL from his country team or some other incident. He also spent time back in the SANFL with Sturt, where he achieved great things with a young Sturt team.

Soaring above a Hawk in the 1977 Second Semi-Final.

In 1991 he reflected on the opportunities he’d wasted. “Certainly I look back and think I didn’t make enough of myself,” he said then. “If I had my time over again I would have changed my attitude completely; I would have stayed at training, been prepared to do all the right things and become a real part of things. I’d just conform a little bit more.”

But the fact that he didn’t has helped make the legend of Phil Carman what it is. He remains an almost mythical figure, largely on the basis of that one extraordinary season and all the bizarre incidents that followed. There are still some who label him the best player they’ve seen at Collingwood – after just 66 games. The fans have long forgiven him for the indiscretions: what they have are memories of a freakishly gifted footballer who could have been anything.

This is an edited version of the story that appeared in the club’s centenary book, A Century of the Best.