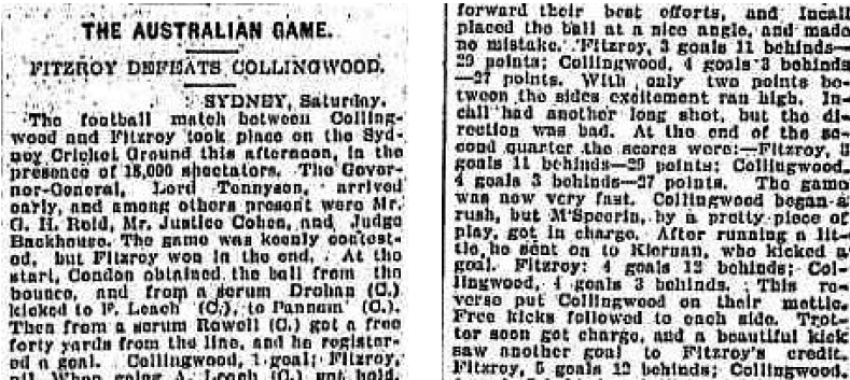

By: Glenn McFarlane

The Magpies' relationship with Sydney, the city, dates back to long before South Melbourne packed up its players and headed to the Harbour City in 1982.

In fact, the club's history dates back 109 years, to what was the first VFL match to be played for premiership points outside of Victoria.

Incredibly, Collingwood and Fitzroy did battle at the Sydney Cricket Ground on May 23, 1903, in a visionary display put on by both of the clubs to push the development of Australian football well beyond its boundaries.

The Magpies had always believed themselves to be innovators in the years after the club's birth in 1892. Much of that came back to developing the club in the suburb that gave it birth. But within a decade of Collingwood's inception, it had the forethought and willingness to take the game to a new audience.

The match, scheduled for Round 4, was organised by the VFL and was originally slated in to be an exhibition clash. But given Collingwood was the reigning premiers from 1902, the club determined that it wanted to play a real match, and it wanted Fitzroy, its biggest rivals, to be the opposition side.

So these two powerful inner-suburban rivals pledged to take the game north and start a national push that was many, many decades before its time.

Collingwood had been content to play its part in history; but its supporters were less than enthusiastic.

Magpie fans had been reluctant to forego seeing their beloved sides in one game, despite the fact that the two clubs had tossed for which team would host the second meeting later in the year, and Collingwood had won.

There was a disapproval motion put to the club's heated annual meeting just prior to the start of the season. But the club stood firm on its decision.

The club's annual report from the following year explained: "Your committee, after the last election, unanimously decided that they would fulfil the promise made by them as Premiers of 1902, to the representatives of the NSW Football League, believing their actions would give great impetus in NSW, and would rebound to the benefit of your club in that state in future years."

Collingwood also believed the chance to take its players away on an interstate trip would be advantageous. One of those among the 1903 touring party, a 20-year-old first year player called Jim McHale, would note the benefits of such tours and how they could galvanise teams and lead to better performances.

In the years to come, they would call him 'Jock', and McHale would use these trips as the catalyst for building camaraderie and mateship to successful teams.

As bold and innovative as the plan was to push the football boundaries, not everyone was enamoured by what was happening.

The Australian Town and Country newspaper of May 27, 1903, headlined the match as "An Invasion of New South Wales." It said: "The visit of the Collingwood and Fitzroy teams to Sydney is the latest attempt to attract the attention of Sydney people towards that form of football which was evolved in Melbourne some 40 years ago. It is an expensive advertisement, for it will cost the Melbourne clubs close on 1000 pounds for expenses."

But football columnist 'Markwell', from The Australasian, was more favourable, saying: "The trouble and expense to which Collingwood and Fitzroy's executive had been put in connection with the undertaking were entirely lost sight of in the consequences of the immense support that had been achieved ... they (the teams) were taken by boat or by drags to all the beauty spots; they were banqueted and feasted to their hearts' content; and they were praised and thanked almost inordinately for the sacrifices in the interest of Sydney football."

For the two visiting teams, there were picnics on the Harbour (the bridge was still a pipedream and 29 years away from opening), a night at Fitzgerald's Circus, a trip to Tooth's Brewery and a "smoke concert" at the Grand Hotel.

And, yes, there was still the football match, which attracted "political and social leaders" as well as the patrons of Sydney to see this strange game that had been long talked about, but rarely seen.

Among the luminaries were Australia's Governor-General, Lord Tennyson; future Prime Minister George Reid; and H.C.A. Harrison, the man considered the father of Australian football.

The crowd was somewhere between 18,000 to 20,000. To make it easier for those in attendance who had no idea as to the identities of those wearing the black and white colours or the maroon and blue, numbers were used on the backs of the players.

Some of those numbers were clearly visible; others were less obvious. But it would be the first time that numbers were used in a VFL match. And it would not be until 1912 that numbers would be included in all matches.

Some of the ambitious advertisements for the Collingwood and Fitzroy clash promised a great contest, declaring "the match will constitute a marvellous and brilliant exposition of the Australian game."

The Referee, a publication devoted to sport and the stage, regarded it as false advertising, saying: "it was a prophecy that was not realised; the match did not show the Melbourne game in its most brilliant aspect."

Perhaps that was right, but just maybe there was also a hint of the cross state rivalry that exists to this day.

In contrast, the Argus recorded: "The pace and dash infused into the play and the brilliant accuracy of the kicking were a revelation ... the buzz of excitement around the ground was such as is heard only when New South Wales and New Zealand are meeting at football or England and Australia at cricket."

What is certain is that both teams had some wonderful players, with some of Collingwood's famous names of the time playing that day, including the highly-talented, but erratic Dick Condon, who had helped to transform the game by fashioning the stab-kick a year earlier, Charlie Pannam (grandfather of Lou Richards), Bill Proudfoot, Ted Rowell, Bob Rush and the club's captain 'Lardie' Tulloch.

Collingwood had the most impressive start to the game, kicking three goals to one in the opening term. The first came from Rowell after Fitzroy had been "penalised at half-forward" and it brought about "amid great cheers."

Then, as the Argus correspondent said, "Excellent passing brought the ball back to ... goal, and Condon securing from a throw-in, kicked the second goal for his side." Ted Lockwood made it three goals for the Magpies, with Fitzroy's only goal for the term coming from Percy Trotter.

Collingwood led by 11 points at the first change, but Fitzroy did all the attacking in the following quarter. The Magpies were "under siege", with only the Lions' inaccuracy stopping them from a much bigger lead than the two-point buffer they had at half-time.

The Lions booted 2.8 to the Magpies' 1.1 for the term, with Collingwood's only goal coming from Jack Incoll, as the beneficiary of a free kick further up the field to George Angus. Incoll's place kick gave those supporting the Magpies some hope at half-time.

But although Collingwood "fought gamely", Fitzroy had secured a clean break on their opponents. Three goals to the Magpies' one (from a place kick from Tulloch) pushed the margin out to 13 points at the last change.

Rowell kicked Collingwood's sixth goal in the last term - and his second for the game - with a "long, accurate kick", but it would all be in vain. Fitzroy won the historic contest by 17 points, and it could easily have been more considered their score line of 7.20 (62) to 6.9 (45).

Collingwood had looked to the greater good - for the sake of football - and it deemed the trip as a success, even if it had not won the four premiership points.

And incredibly, as the club's annual report recorded, "the return journey was broken at Rutherglen, where a match was successfully played (against a Rutherglen and district side), and generous hospitality enjoyed." The Magpies had no trouble winning that contest - 9.12 (66) to 5.9 (39).

Collingwood would not lose another game for the rest of the 1903 season, as well as having the last laugh on its Sydney conquerors, Fitzroy. The Magpies would win the return match at Victoria Park by 20 points, and then the Grand Final by two points after Fitzroy star Gerald Brosnan missed a shot after the final bell.