By: Glenn McFarlane

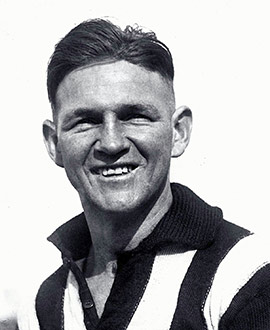

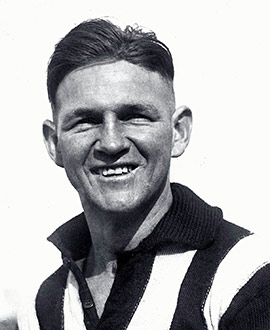

Albert Collier was only 20 when he won the Brownlow Medal. His older brother, Harry, was almost 82 when he put his Brownlow Medal around his neck.

How that happened is a part of the rich tapestry of Australian football's highest individual honour, and it remains one of the more heart-warming stories associated with the game.

Harry Collier watched with pride when his sibling won the 1929 medal; and he was shattered when he tied for the 1930 medal with Richmond's Stan Judkins and Footscray's Allan Hopkins only to lose it on a countback.

It was only due to Collier's dogged determination and persistence that he was able to right a Brownlow Medal wrong almost 60 years after the fact, not just for himself, but for others who had been denied their rewards.

The 1930 medal count took place on Wednesday, September 17, with no clear resolution over how the league would resolve what ended up being a three-way deadlock, with each player receiving four votes.

The Argus described the dilemma: "There has never before been a tie, and the committee will have difficulty in deciding the destination of the Brownlow Medal, which is awarded to the winner."

There were several delays and at one stage it appeared as if the league might either award three medals, even though part of the constitution of the award determined that there could only be one winner.

Then, the recommendation of the permit and umpires committee recommended that there be no winner of the award for the season.

Tellingly, there were three informal votes. The most controversial was the one that simply read: "Collier" without differentiating between the Magpie rover/forward Harry and his bigger, defender brother Albert.

The Magpies would allege later that the umpire had said he intended it for "the little rover fella".

On the eve of Collingwood's first final, Richmond's delegate, H. L. Roberts claimed the Brownlow Medal rule stated: "The player attaining the largest percentage of votes to games played (was) to receive the award."

As such, VFL president Dr. W. C. McClelland declared Judkins as the outright winner, as the Richmond wingman had played fewer games (12) than Collier (18) and Hopkins (15).

The Argus explained: "Dr McClelland ruled that in the spirit of the rule, the medal should be awarded, but that some revision of the regulations was advisable."

Collingwood was furious, and so was Collier. Years later, he would say without malice: "Not meaning anything against Judkins, but comparing him with Hopkins and myself was ridiculous."

Collier and the club would fight to claim his share of the medal for decades. Periodically, they would raise the matter with the VFL, and he made another passionate plea at the 1988 VFL annual general meeting.

The following year he would receive one of his most memorable phone calls – from the league.

The league had decided to strike retrospective medals for those footballers who had lost in Brownlow countbacks. Collier would finally get his medal, as would 86-year-old Hopkins, at a gala celebration in 1989.

"I got a terrible surprise, a happy surprise, I was really shocked," Collier said of the phone call that provided him with the news.

"I was home there with my wife (Verna) just about to have some tucker and I couldn't eat me tucker after that."

Collier's season - his fifth - was an outstanding one almost from the start of the season as the rover-forward played a significant role in the club's success.

One of his biggest games came in Round 6 against North Melbourne, when the Argus said full-forward Gordon Coventry owed much of his goalkicking success that day to the busy Collier, "to whom the state of the area and the slippery ball were no handicap."

He was vying for best afield honours a week later with his captain Syd Coventry, with one observer saying his "work forward and roving was brilliant."

A string of outstanding individual performances in successive weeks against Carlton in Round 10 and Essendon in Round 11 put him at the forefront of the umpire's attention.

Collier's efforts against the Blues when roving was described as "outstanding", while he was just as impressive in the mud against the Bombers a week later.

And his only challenger to the Brownlow vote on offer in the Round 12 game against Fitzroy was full-forward Gordon Coventry, who kicked a club record 17 goals. It was said Collier was "a champion ... whose skills, brains and dash made him conspicuous".

In Round 14 against Melbourne, "Collingwood had not a weak man in the colours, but I think pride of place should be awarded to H. Collier (roving)."

And in the game against Footscray two weeks later Collier kicked four goals and was once more listed as his team's best player.

Harry Collier had to have waited until 1989 for his just rewards, but he deserved the honour long denied him. Sadly, his brother, Albert, would not be around to see them installed as the only set of Brownlow Medal brothers, as he had died a year earlier.