For a young man who was the son of arguably our greatest ever captain, and definitively one of our greatest ever players, Hugh Coventry crept into the Collingwood Football Club quietly, and almost by accident.

He had been playing with Ivanhoe Amateurs for a couple of years, but midway through 1940 the whole amateur competition disbanded because of the Second World War. So Hugh wandered along to Collingwood’s reserves side and played out the rest of the season there, being part of a Premiership side.

In April of 1941 he enlisted with the RAAF, and then played the 1941 VFL season while waiting for his call-up. Again he played seconds, but was also called up for eight senior games. He started his service in November, and that was pretty much the end of Hugh’s elite football aspirations.

For someone who was a member of arguably Collingwood’s most famous family at the time, it was a low key entrance to and exit from the game. Not what might have been expected when things began.

Hugh was born in Clifton Hill, the oldest of four sons of the legendary Syd Coventry. The second oldest, Jack, was also a handy footballer and played with Collingwood seconds, while the third-born, Syd Junior, would end up playing seven senior games with the Pies in the 1950s.

Hugh’s early life was filled with footy, cricket (there was a ground called Millers Flat near their home), tennis and horse riding. He was also a reluctant pianist, until a fight with Jack ended with the latter being hit over the head with his violin, while Jack in return jammed Hugh’s fingers in his piano top. He first went to Fairfield State School, then on to Melbourne Technical College and from there started work as a Survey Draughtsman at the Melbourne Metropolitan Board of Works, where Syd also worked.

His love of football was no surprise: as a small boy he’d seen the famous Machine win their four flags in a row, with dad Syd as captain and uncle Gordon as gun full-forward. Hugh didn’t quite share their footballing ability but he was a good player nonetheless, and he did well enough at Ivanhoe to transition into life at Collingwood seamlessly.

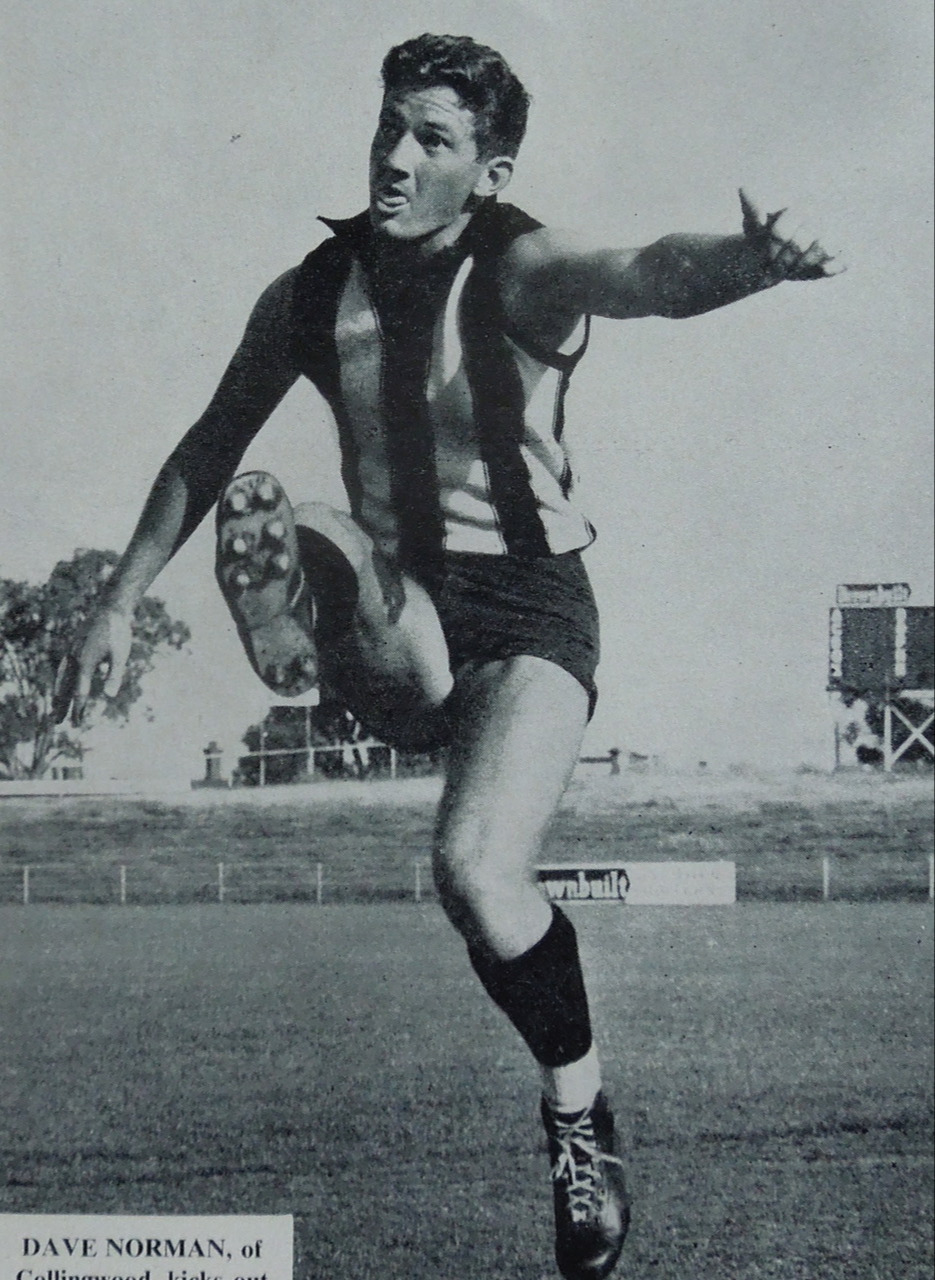

He played mostly on a half-forward flank in his senior games, and after he debuted in that position against St Kilda in Round 9, quickly made a name for himself. The Sporting Globe noted after that debut game: “He did well enough in the first half to suggest more games with the Magpies. He has a remarkable resemblance in build and mannerisms to his uncle Gordon, champion goalkicker of all time.”

He kicked four goals in just his third game, against Richmond in the wet, and followed it up with further bags of two, three (after starting on the bench) and two. This was a kid who clearly knew where the goals were.

The press were quick to jump on his performances. “The name of Coventry seems destined to remain with Collingwood for a long time,” wrote The Weekly Times. “On Saturday, Hugh Coventry … nephew of Gordon, the greatest forward the game has known, scored four goals. At first he was stationed on the half-forward flank, but did not show up. Transferred to a forward pocket, he immediately got among the goals. His style of kicking is strongly reminiscent of his uncle.”

The Sporting Globe similarly noted his impact in that Richmond game. “Hugh Coventry proved he is the son of his father by taking full advantage. Young Hugh, who has graduated through the Amateur ranks and the Collingwood Seconds, is now more the physical stamp of his uncle Gordon than his father. The game on Saturday had swung against Collingwood. Then an unexpected break came their way. Young Coventry made an opening and the ball was shot across to him. Everything depended on his kick—not an easy angle with a wet ball. He rammed it down. The move was repeated—again he rammed home the ball. Then moving across the goal he was forced to kick as they scragged him. Over he went with the Richmond defenders on top of him, but he had sent his kick home straight and true. Collingwood were back in the game and winning. Still again he scored with the same deliberate coolness. Those four goals won the game for Collingwood.”

Four weeks later, against Melbourne, his marking was described as ‘brilliant’. “Some of his marks had that touch of class about them that was reminiscent of his famous Uncle Gordon,” wrote The Sporting Globe.

All in all it was an excellent debut campaign for Hugh, and one which held plenty of promise for what might be to come.

But then the War intervened.

He entered training school for the RAAF at Somers in 1941, then headed to Canada and Britain for further training. He would eventually be attached to the RAF 149 Squadron and later 199 Squadron. Hugh would pilot the huge 4-engine Stirling bombers for 42 missions over France and Germany. These flights involved bombing road and railway infrastructures and depots, laying shipping mines, supply drops for the French resistance and laying decoy target trails.

When he had finished his two ‘end-on-end’ tours with Bomber Command, Hugh switched to Transport Command, and was relocated to the Asia-Pacific conflict area. Now flying DC-3 aircraft and with his home base in Brisbane, Hugh spent the final 15 months of his service doing trips to New Guinea, Indonesia, the Philippines, Hong Kong and Singapore. By 1945 he was a flight lieutenant, and he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for 'skills and fortitude in operations against the enemy in the course of which he has invariably shown the utmost fortitude, courage and devotion to duty’.

Hugh remained stationed in Brisbane when the war ended but was not discharged until May 1946. He returned to Melbourne – and to Collingwood, where he resumed playing with the reserves. Together with his brother Jack he played in a reserves preliminary final later that year.

He was looking forward to seeing if he could return to his pre-War form and regain his place in the seniors – he was still only 24, and was confident he could – but the Magpies advised him he was likely to struggle for selection in 1947. Disappointed, he headed to Brisbane, where he spent two seasons with Western Districts. He and his family – he was by this stage married with two kids, which would later become three – then returned to Melbourne, but only briefly.

Former Magpie teammate Alex Denney, who had played 35 games with us in the late 1940s, then stepped in. Denney had a connection to Hugh because he had married Gordon Coventry's daughter Betty. Alex was a brilliant footballer in his own right but was a farmer in Wycheproof who turned his back on the VFL because he could not afford to be away from the land. So Alex tempted Hugh with the promise of football, a job and a wonderful lifestyle.

Hugh jumped at the chance, and started a highly successful five-year stint as captain-coach of Wycheproof in the North Central Football League (NCFL), from 1950-54. He stayed for 1955 as a player only, then spent a year as captain-coach of Berriwillock in the Tyrrell League, leading them to a flag, before returning to Wycheproof for one final season in 1957. In all he played in four flags while with Wycheproof. When his playing career ended, and with limited secondary schooling opportunities available for his children, he returned to Melbourne, settling in Greensborough.

Hugh Coventry was always going to have his work cut out matching the careers of his father and uncle. But all the early signs suggested that he was well on the way to being able to forge his own path, with his own successes, before the Second World War got in the way. He was far from the only one to suffer that fate, of course, but it must have been frustrating nonetheless.

- Michael Roberts